On Seeking Home & Freedom

“I have been a stranger in a strange land.”

– The Bible

Exodus 2:22

The story of Passover is a commemoration of the exodus of the ancient Israelites from slavery to freedom. It’s about the journey of a group of people wandering difficult landscapes in search of a place to live with dignity — in search of home.

As an Iranian-American Jewish Woman, my relationship with religion is complex. But I appreciate the holiday’s universal themes of memory, optimism, humanity, family and our responsibility to each other.

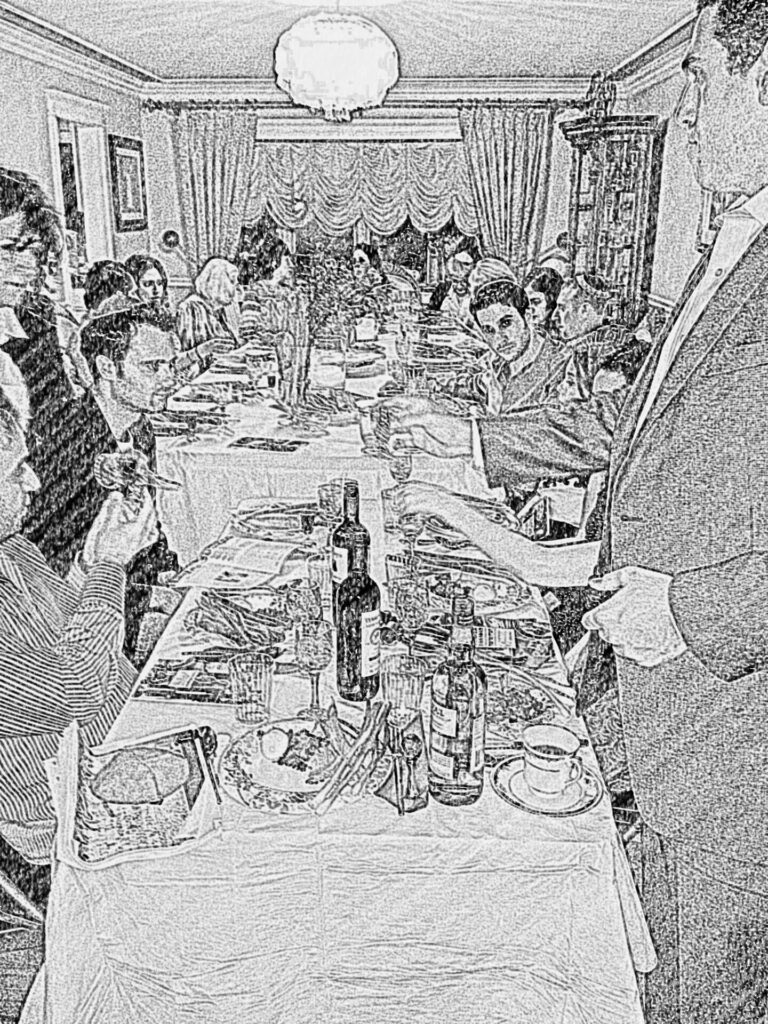

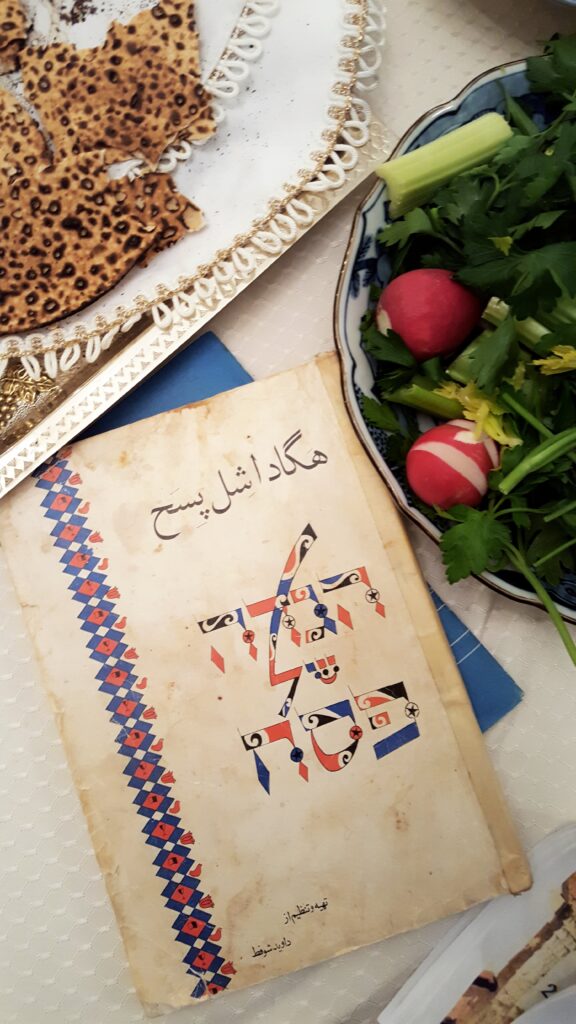

This passover, as done for generations, my family sat at a long table and performed symbolic rituals in a specific order, reading from a Hebrew and Farsi prayer book. At the core of this process is the retelling of the exodus story. A 3,000 year old tale repeated every spring, for thousands of years. Why is this story different from other stories?

Storytelling performs an important role in human societies. Aside from broadcasting social norms to coordinate social behavior and promote cooperation, stories are our human super power. We tell stories to survive, to build and to thrive. To remind us that we are not alone in the world. We construct internal narratives to make sense of the complexities of life and we tell chronicles collectively to find certainty in an uncertain world.

Given that, one has to contemplate the merit and utility of a story that has lasted for three millenia. The biblical story of Passover is the ultimate story of human perseverance, of faith, of humanity surviving against improbable odds, and ultimately, it is the story of freedom.

In Farsi Passover is referred to as the Holiday of Freedom (“eid-e azaadi”). Today this resonates more strongly than ever in a world embroiled in a refugee crisis with millions of innocent people displaced, wandering, and in search of stability. People from Syria, Afghanistan, Central America, South Sudan, Myanmar, Ukraine and beyond. Not to mention how the Covid-19 Pandemic exasperated many of society’s inequalities and displaced vulnerable communities in other devastating ways.

This year, the notion of fighting for Freedom rings evermore for the people of Iran as they bravely demand basic human rights from an evil regime which will go to unthinkable lengths to maintain power. Today Iranians are fighting for the right to live and love openly, and they bleed on the streets for agency over their lives. They’re fighting for women, for life and for freedom. The protests in Iran resonate with me personally. After all my parents escaped those same circumstances, aptly naming my sister “Azadeh” — meaning one who has been freed in Farsi — when she was born shortly before our painful departure from Iran, forced to leave the only home they had ever known. And while my own childhood memories are heavily pained by that exodus, I know this saga is not unique to Iran and Iranians.

The malign powers of the regime in China, the world’s most populous dictatorship continues to ramp up censorship. Individuals in North Korea live in the dark. Long standing conflicts continue in Libya, Yemen, Ethiopia and Azerbaijan – to name only a few – forged on by greedy authoritarian leaders to resolve petty political disputes. I am not an expert in the complex dynamics of these affairs, but I know millions of innocent people are kept hostage, their freedoms reduced to nothing at the whims of egocentric dictators. Or as Carl Sagan put it “think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that, in glory and triumph, they could become momentary masters of a fraction of a dot in the universe.”

The story of Passover is also central to America’s conception. You can see how the themes of the exodus have inspired various American leaders. From the founding fathers, to abolitionists, and civil rights leaders in the last century. American abolitionist, former slave and “conductor” on the Underground Railroad, Harriet Tubman was known to many as “Mother Moses.” She used spirituals such as “Go Down Moses” to signal slaves that she was in the area to help those who wanted to escape. Afterall, America is the “promised land” my family traveled to from the atrocities of the Islamic Republic of Iran and an eight-year Iran-Iraq war that senselessly destroyed everything for nothing.

So the exodus story lies at the heart of who we are as people. We have all been a stranger in a strange land. Misunderstood, lost and in search of a home where we can be free to be ourselves, without punishment and perdition. The 3,000 year old story of seeking freedom reverberates in the spirit of many nations, and in the heart of every human being. It echos the dream of leaving subjugation to find freedom. Rebelling against tyrants to obtain the power to act, speak, or think without restraint.

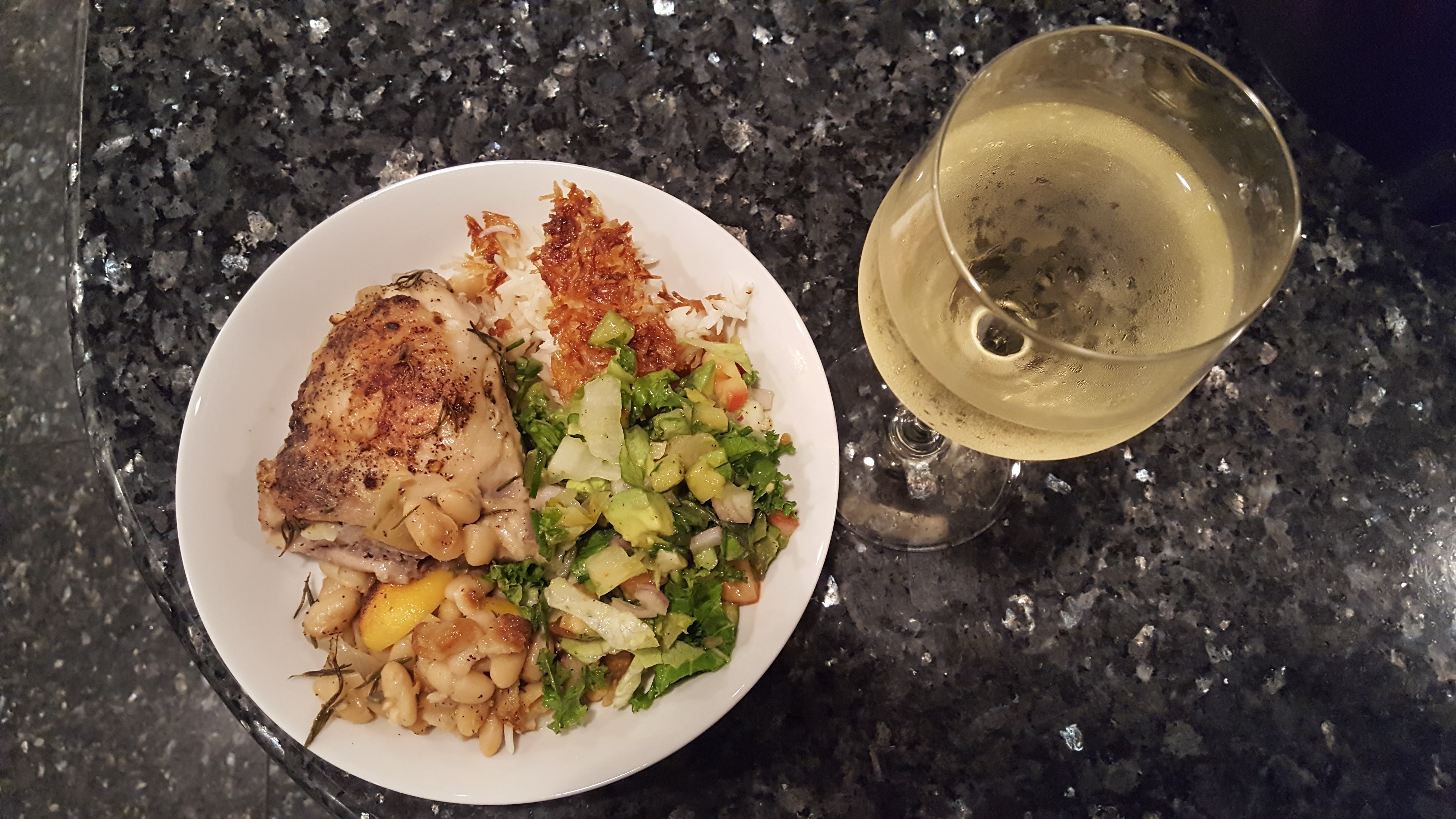

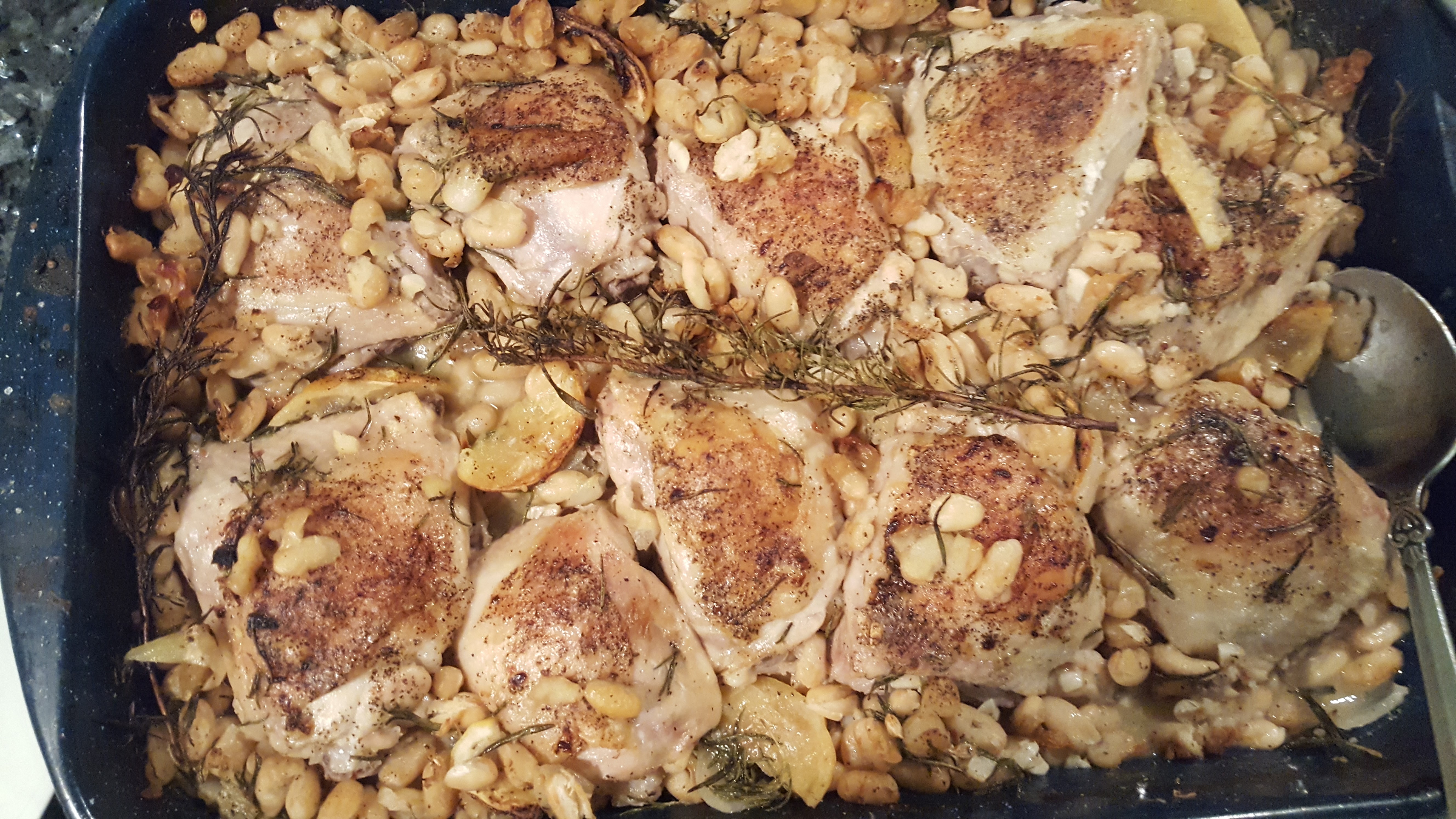

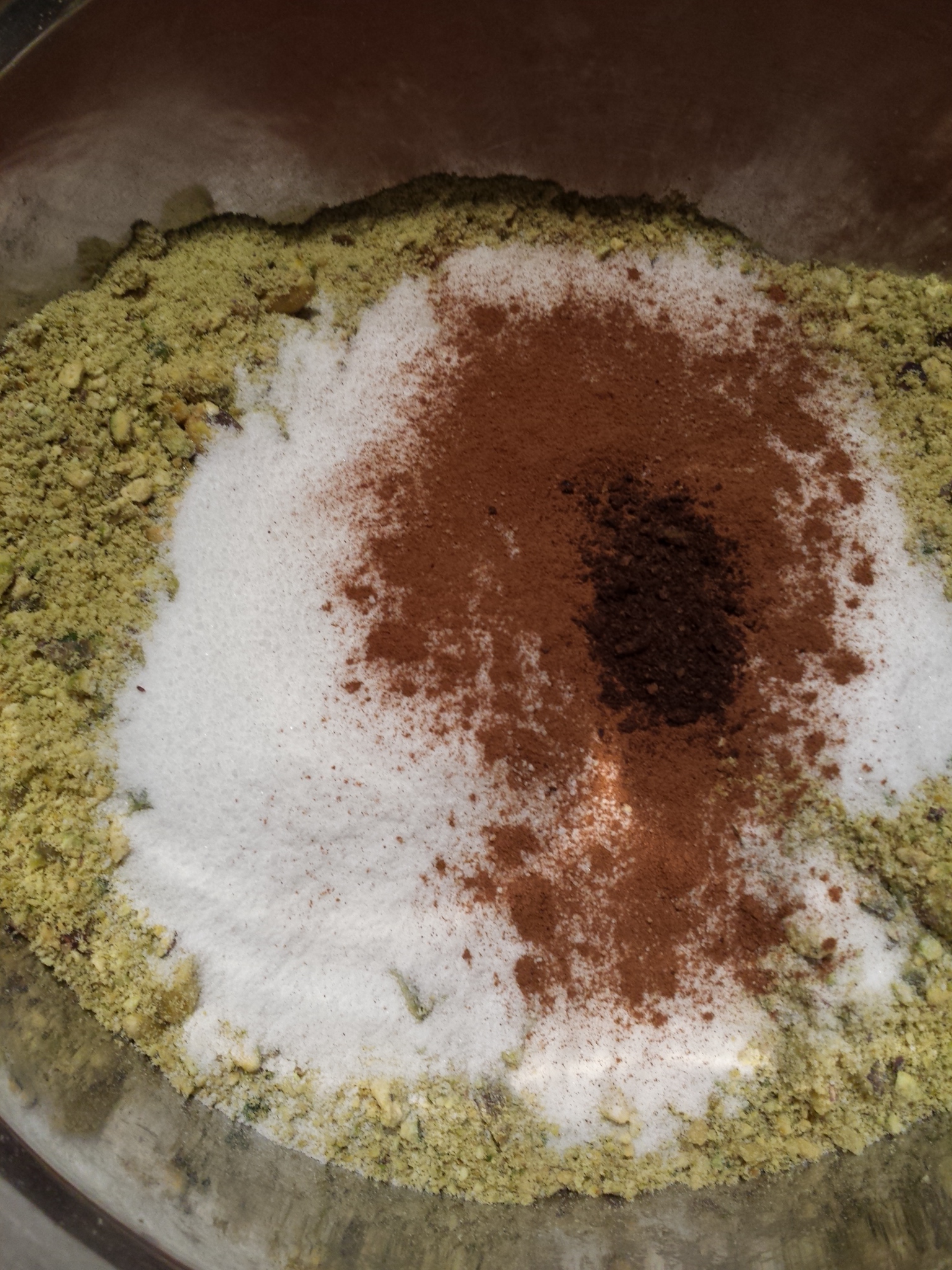

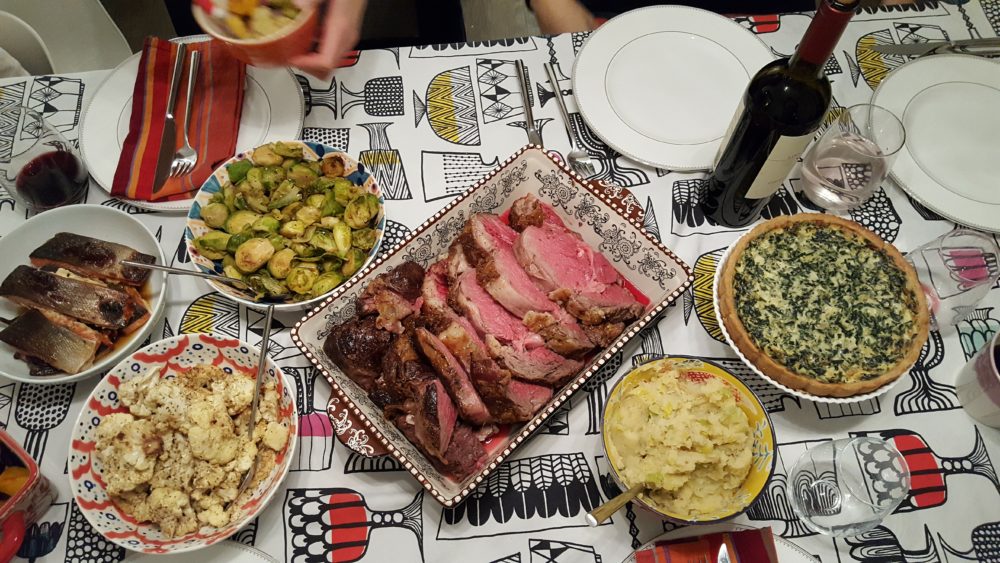

We may not have the solutions to these issues today, but we can talk about them, at our dinner tables and elsewhere. Stand up against modern-day pharaohs, with our disapproval. I hosted a Passover seder at my NYC apartment this year. I had the luxury of stressing over the menu, not enough folding chairs, and if the brisket would be ready before sundown. But I grew up in Iran and I know from generations of discrimination and difficulty, how many others are spending this holiday across the globe – life challenges far bigger than the timeliness and contents of a meal.

This year Nowruz, Passover, Easter and Ramadan all coincided. The universal themes of all of these holidays are the same: renewal, faith, freedom, sacrifice, charity and community.

Just as in the Jewish tradition, all of these holidays are about coming together and meeting adversity with optimism and generosity. The similarities in the human quest for meaning are not a coincidence. The observers and rituals may be different, but the common denominator is a festive meal to cement our values of humanity and hope. With these shared values, we can all come together and learn from one another. It is an opportunity to celebrate kindness and foster respect. Of course symbolic foods play a role in all of our celebrations as we break bread, break barriers and build bridges.

The shared meal is an act of love. No matter what your style, customs or origin story, when we gather to enjoy a meal, we are unified in engaging in a tradition as old as humanity — one which transcends national borders and cultural divides.

Wishing for Freedom and joy wherever a human heart beats, with hopes that good people all over the world have the opportunity to gather with their loved ones, just as we did this week.

Can I get a hallelujah?

“Not Christian or Jew or Muslim, not Hindu, Buddhist, Sufi, or Zen.

Not any religion or cultural system. I am not from the east or the west, not out of the ocean or up from the ground, not natural or ethereal, not composed of elements at all.

I do not exist, am not an entity in this world or the next, did not descend from Adam and Eve or any origin story.

My place is the placeless, a trace of the traceless. Neither body or soul.

I belong to the beloved, have seen the two worlds as one and that one call to and know, first, last, outer, inner,

only that breath breathing human being.” ~Rumi

~ Musical Inspiration ~

American abolitionist, former slave and “conductor” on the Underground Railroad, Harriet Tubman (known to many as “Mother Moses”) used spirituals such as “Go Down Moses” to signal slaves that she was in the area, and would help any who wanted to escape.

Cindy’s Fabulous Holiday Rib Roast (Recipe coming soon)

Cindy’s Fabulous Holiday Rib Roast (Recipe coming soon)